Mouthing its typical anti-wage hike stance at a time of rising prices driven by the government’s inflationary tax “reform,” the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) recently reiterated its quite “matapobre” (very anti-poor) and ala-Marie-Antoinette declaration that a Filipino family of five can live decently on 10,000 pesos per month.

The said amount is the Philippine government’s outrageously outdated official poverty line. As per the government’s perspective, a family is deemed poor if it lives BELOW the poverty line – which means, according to the government, a Filipino family of 5 is only considered poor if it lives on amount below 10,000 pesos monthly. More outrageously, that also means that a Filipino family of 5 that lives on an amount within or above 10,000 pesos monthly IS NOT CONSIDERED POOR.

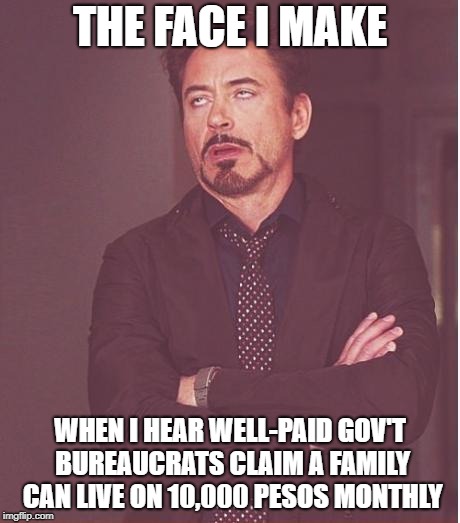

We can choose to forget the inconvenient fact that the NEDA Undersecretary who bravely babbled the aforementioned anti-poor insult receives a monthly salary of something between 96,354 to 175,184 pesos (from us poor taxpayers of course), and focus on what is obvious: A FILIPINO FAMILY OF 5 CAN’T LIVE DECENTLY ON 10,000 PESOS PER MONTH. The following segments are from a paper that I have co-authored, and will be presented in a conference this year.

I urge you to read and repost this to help counter the lies peddled by NEDA and other government agencies in the malevolent defense of their anti-wage hike and anti-TRAIN 1 reversal stance

Critique of Official Philippine Poverty Statistics

Official Philippine poverty statistics should be subjected to a rigorous critique, if the real extent of poverty is to be revealed as a springboard for realizing the actual breadth and depth of poverty as a national and international problem, which is the first step towards genuinely resolving the problem.

At the outset, the critique could begin with backing up Chossudovsky’s (2018) straightforward way of describing official poverty figures in the Philippines as something that “have been manipulated” as the Philippine government only appears to have “adopted the one dollar a day World Bank criterion” while failing “to account for inflation in both the 2012 and 2015 estimates.” Such official Philippine poverty statistics focus too much on food poverty and fails to adequately encompass other essential people’s needs. Moreover, these statistics don’t consider the fact that families can be food-rich (with incomes deemed officially high enough to cover the minimum food threshold set by national authorities) and actually poor at the same time.

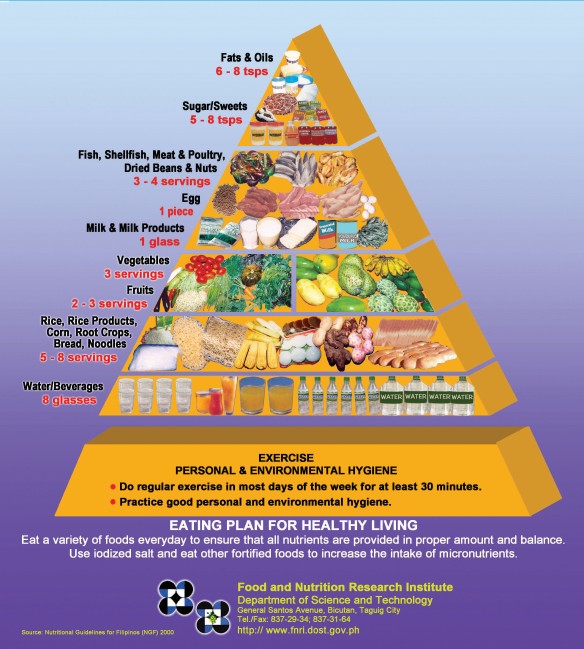

Even the official food poverty threshold cannot accurately measure real levels of food poverty, as it has been shockingly and significantly redefined in 2009. Such recalibration of the food poverty threshold imposed lower and thus cheaper dietary requirements for Filipino citizens, thereby artificially lowering down the official poverty statistics. The new food poverty threshold was so laughable that it was eloquently criticized even by a mainstream statistician who correctly spotted the wide gap between the old and the new methodology for measuring food poverty (Mangahas, 2011a). For example, Mangahas (2011b) notes that the new menu for the food threshold includes “no meat” for the poor (see Table 1), despite the Philippine government’s inclusion of meat in the country’s “Daily Nutritional Guide Pyramid” released by the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (see Figure 1).

Table 1. Old and New Menu in the Philipppines’ Official Food Poverty Threshold (Mangahas, 2011b)

| Meal | Old Menu | New Menu | Changes |

| Breakfast | · Tomato omelette

· Coffee for adults · Milk for children · Fried rice |

· Scrambled egg

· Coffee with milk · Boiled rice |

· Elimination of tomato

· Elimination of milk for children · Substitution of fried rice with boiled rice |

| Lunch | · Fried galunggong

· Mongo guisado with malunggay leaves and small shrimps (mung beans sauted in garlic, onion, tomatoes, malunggay leaves and small shrimps) · Boiled rice · Banana latundan |

· Mongo guisado with malunggay leaves and dried dilis (mung beans sauted in garlic, onion, tomatoes, moringa leaves and dried anchovies)

· Boiled rice · Banana latundan |

· Elimination of fish

· Substitution of small shrimps with dried dilis |

| Dinner | · Pork adobo (pork cooked in vinegar, soy sauce, garlic, and black pepper)

· Pechay guisado (sauted bok choy) · Boiled rice · Banana latundan |

· Fried tulingan (bullet tuna)

· Boiled kangkong (swamp cabbage) · Boiled rice |

· Elimination of pork

· Substitution of pork adobo with fried tulingan · Substitution of pechay guisado with boiled kangkong |

| Snacks | · Pandesal (small common bread) with margarine | · Plain pandesal | · Elimination of margarine |

Fig. 1 Daily Nutritional Guide Pyramid for Adults (Food and Nutrition Research Institute, c. 2018)

As per the latest (2015) official poverty statistics released by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), “a family of 5 needed at least 9,064 pesos (US $174) to meet both basic food and non-food needs monthly” of which 6,329 pesos (US $122) is allotted “to meet basic food needs,” allowing only for a meager 2,735 pesos (US $ 53) for “non-food needs.” Such pitiful amount for the non-food needs won’t cover all the items enumerated by a 2007 resolution of the country’s National Statistical Coordination Board (NSCB): 1) clothing and footwear; 2) housing; 3) fuel, light, water; 4) maintenance and minor repairs; 5) rental of occupied dwelling units; 6) medical care; 7) education; 8) transportation and communication; 9) non-durable furnishings; 10) household operations; and 11) personal care & effects.”

At this point, we should emphasize that NEDA’s figure for the monthly food expenses of a family of 5 (a measly 3,834 pesos) is fantastical, if not downright fictional, and it also WAY BELOW the Philippine Statistics Authority’s own estimates (6,329 pesos, which is also fantastical, as explained above). Which makes us all wonder, is NEDA still serving our people’s interest, or it is now a fabricator of a genre which we can label as economic fiction?

Furthermore, it must be noted that the Philippine government’s categories of essential non-food items doesn’t include any item related to leisure/entertainment, despite the fact that the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (for which the Philippines voted in favor) mentions “the right to rest and leisure…” in Article 24. Other entities such as the European Union’s Eurostat (2015) includes leisure in their “quality of life indicators.” This laudable inclusion is a reflection of the generally accepted idea that leisure is an essential human need (Leversen et al., 2012, and Veal, 2015). Thus, a genuinely holistic poverty threshold should certainly include leisure-related items in the essential non-food items. Establishing such holistic poverty threshold will certainly categorize most Filipinos as poor, contrary to the government’s claims.

Alternative Measures of Poverty

Poverty thresholds should always include thresholds on essential non-food needs of the people. Poor citizens are those whose incomes are below the real cost of living. To help present a better view of real poverty rates in the country, the current researchers made an updated (and still very conservative) estimate of the government’s categories of non-food items based on actual Metro Manila prices:

Table 2. Detailed Monthly Cost Estimate of Non-Food Items for A Family of 5 In the Philippines (2018)

| Non-Food Item | Cost for a Family of 5 | Assumption/Explanation | Source of Data |

| Clothing and footwear | 192 pesos | Assuming the family needs only two sets of clothes and footwear per year and costs are spread per month

Cheapest price for t-shirt, blouse, skirt, shorts and jeans (only for the father) in the popular Divisoria Market

Cheapest price for shoes (only for mother and father) and slippers (for the whole family) in the popular Divisoria Market |

Price watch of the government TV Channel, People’s Television/PTV (2016a and 2016b) |

| Housing or

rental of occupied dwelling units |

9,000 pesos | Cheapest monthly rent for unfurnished studio unit in Manila (apartment prices are definitely higher) | Researchers’ own canvassing of April 2018 rent prices in Manila (listed prices in online rent advertisements are higher) |

| Fuel | 415 pesos (LPG)

|

7-kg. LPG tank

|

Department of Energy (2018)

|

| Light | 1,255 pesos (light and basic applicances)

|

3-hour daily use of one florescent lamp; daily use of small refrigerator; 15-hour/day use of ceiling fan; 8-hour/day use of small TV

|

Manila Electric Company (MERALCO) online app (2018)

|

| Water | 122 pesos (water, not for drinking)

140 pesos (drinking water)

|

10 cubic meters of water

20 gallons of drinking water/month (common brands)

|

Maynilad Bill Calculator (2018)

Researchers’ own canvassing of April 2018 prices in Manila |

| Maintenance and minor repairs | 250 pesos | Monthly cost of low-cost plumbing repair service (assuming repair is only done once a year) | Gawin Group (2017) |

| Medical care | 375 pesos | Monthly cost of QualiMed AKcess Card for the family, “an affordable primary care health card used to avail of free healthcare service inclusions and discounts on outpatient or ambulatory care needs” | QualiMed (c.2018) |

| Education | 3,000 pesos | Covers only cheap school lunches for 3 children per month (assuming that children study in public schools where tuition is free and books are provided for by the government) | Researchers’ own canvassing of April 2018 prices in Manila |

| Transportation and communication | 480 pesos

700 pesos |

Covers only minimum jeepney fares per month for 1 person (assuming that the family lives in the town center and only the father commutes daily to work)

Covers only cellphone load for two people (one-month unlimited calls to the same network and unlimited text to all networks) |

Fare price set by the government

|

| Non-durable furnishings | 0 | Prices of covered tems are difficult to estimate; hence no estimates are given | N/A |

| Household operations | 2,000 pesos | Cheap laundry expenses (for 80 kilos of laundry/month)

Actual costs for household operations are higher as prices of other covered items and services are difficult to estimate; hence only estimates for laundry |

Researchers’ own canvassing of April 2018 prices in Manila |

| Personal care & effects | 162 pesos | Bath soap (family size) at 4 bars per month

|

Department of Trade and Industry (2018) |

| MONTHLY TOTAL FOR NON-FOOD ITEMS | 18,091 pesos

|

||

| PH GOVERNMENT’S COMPUTATION FOR FOOD ITEMS | 6,329 pesos

|

||

| TOTAL MONTHLY EXPENSES FOR A FAMILY OF 5 | 24,420 pesos

|

||

The researchers’ figures for a conservative but reliable poverty threshold is thus pegged at 24,420 pesos per month for a family of five. Such amount is more than double the government’s official poverty threshold, and a bit comparable with the 33,570-peso monthly living wage for a family of six as computed (albeit without available details on costs) by Ibon Databank (2017), an independent think tank. Websites such as numbeo.com that produce statistics through crowdsourcing, can also help set the poverty threshold. As of April 2018, in what could be dubbed as the upper limit of cost of living in Manila for a four-person family, numbeo.com pegs the figure at 90,858.11 pesos without rent, while monthly rents for one-bedroom apartments range from 12,005.95 to 23,076.92 pesos. Such estimates are actually closer to another government agency’s statistics.

The National Economic Development Authority (NEDA) did release its own statistics on what income is needed for a family of four to be able to live comfortably in the Philippines. Its 120,000-peso monthly figure impressively goes beyond the official poverty threshold, but the same agency downplayed the possibility of the government working towards the concretization of such ideal, emphasizing in its launch that it is just a “vision” and “not meant to be prescriptive. This is just saying where Filipinos want to go…” (Dela Paz, 2016). Nevertheless, NEDA also whimsically claims that the Philippines can attain upper middle-income status as early as 2019 (Leyco, 2018), despite the fact that the government is actually still in denial with regard to the breadth and depth of poverty in the Philippines.

Countless life stories of globalization’s discontents, life stories of marginalized citizens whose lives are not documented by the government’s limited statistics, life stories of poor citizens in one of Southeast Asia’s worst countries with regard to outward migration, poverty, and unemployment rates, could serve as counterpoints to the official narrative and reveal the hidden faces of poverty in the country.

BONUS SEGMENT: Here’s a list of our “favorite” DDS team members and their monthly incomes (just to see how much their incomes are, compared with the 10,000 pesos monthly income which they consider as decent for a family of 5).

| Position | Current Occupant | Average Monthly Salary and Allowances (based on latest COA report unless otherwise specified) | Amount in Excess of 10,000 pesos monthly |

| President | Rodrigo Duterte | 222,278 pesos | 212,278 pesos |

| NEDA Director General | Ernesto Pernia | 168,788 pesos | 158,788 pesos |

| DBM Secretary | Benjamin Diokno | 178,301 pesos | 168,301 pesos |

| DOF Secretary | Carlos Dominguez III | 174,112 pesos | 164,112 pesos |

Lest we forget, Pernia, Diokno and Dominguez released a joint statement yesterday opposing the popular clamor for TRAIN 1’s reversal. Pernia, Diokno, and Dominguez are also against a wage hike. Yep, the same people who say workers don’t deserve a wage hike are the same people who receive very good salaries from our taxes.

We should all clamor for their RESIGNATION NOW or THE REDUCTION OF THEIR SALARIES to merely 10,000 pesos monthly.

(P.S. In computing the average monthly salary and allowances for positions where there were multiple occupants for a year, the total salary and allowances received by the occupants were added and the combined amount is divided by 12.)